Illuminating the Dark Side of Occupation

Illuminating the Dark Side of Occupation

This article aims to introduce the concept of the dark side of occupation and encourage the reader to consider the dynamics behind occupational engagement.

Dr Claire Hart

Assistant Professor in Occupational Therapy

Northumbria University in Newcastle

Primary research field: Refugee mental health and the occupational needs of marginalised groups

The dark side of occupation

Occupational therapy has spent decades presenting a message on the value of occupation for health. The benefits from participation in meaningful and dignified occupation are increasingly well established (Hammell, 2018; Reitz & Scaffa, 2020). However, in our efforts to strengthen these claims we have avoided or ignored occupations which may be personally or socially problematic (Twinley, 2020). In a discourse all about positive occupations and positive outcomes there has been little space to hear about alternative experiences of occupation (Hart, 2017; Nicholls & Elliot, 2019).

The concept of the dark side of occupation is one way in which theorists are challenging some of the assumptions made about occupation by encouraging a broader appreciation of the complex nature of people’s meaningful engagement. This article aims to introduce the concept of the dark side of occupation and encourage the reader to consider the dynamics behind occupational engagement.

The dark side of occupation was introduced by Dr Rebecca Twinley, Senior Lecturer, University of Brighton, UK. She highlighted how a range of occupations have traditionally been under-explored and poorly understood, often because they did not support the narrative of a positive causal relationship between occupation and health (Twinley, 2017). These occupations may not be prosocial, healthy or productive, but they may still have meaning and purpose to the individual (Kiepek & Magalhaes, 2011; Twinley & Addidle, 2012).

In the use of the term “dark side of occupation” Twinley sought to acknowledge the lack of attention to the occupation, and the resultant lack of understanding, not pass judgement on the occupations themselves. As a result, occupations are not described as dark per se, but inhabiting an unilluminated place in our professional attention (Twinley, 2017; 2020). Some specific occupations, as diverse as substance misuse (Keipek et al, 2022), beauty pageants (Sy, Martinez & Twinley, 2021) and sex work (Huglstad et al, 2020) have been linked with the dark side of occupation. However, many occupations have the potential to be explored using this lens. Occupations may be in the shadows for many reasons (Nicholls & Elliot, 2021) and what shapes perceptions of an occupation is often nuanced. Attitudes can reflect the nature of the occupation itself, the way the person engages with it and external attitudes towards the occupation or the person performing it.

This article aims to introduce the concept of the dark side of occupation and encourage the reader to consider the dynamics behind occupational engagement.

Dr Claire Hart

Assistant Professor in Occupational Therapy

Northumbria University in Newcastle

Primary research field: Refugee mental health and the occupational needs of marginalised groups

The dark side of occupation

Occupational therapy has spent decades presenting a message on the value of occupation for health. The benefits from participation in meaningful and dignified occupation are increasingly well established (Hammell, 2018; Reitz & Scaffa, 2020). However, in our efforts to strengthen these claims we have avoided or ignored occupations which may be personally or socially problematic (Twinley, 2020). In a discourse all about positive occupations and positive outcomes there has been little space to hear about alternative experiences of occupation (Hart, 2017; Nicholls & Elliot, 2019).

The concept of the dark side of occupation is one way in which theorists are challenging some of the assumptions made about occupation by encouraging a broader appreciation of the complex nature of people’s meaningful engagement. This article aims to introduce the concept of the dark side of occupation and encourage the reader to consider the dynamics behind occupational engagement.

The dark side of occupation was introduced by Dr Rebecca Twinley, Senior Lecturer, University of Brighton, UK. She highlighted how a range of occupations have traditionally been under-explored and poorly understood, often because they did not support the narrative of a positive causal relationship between occupation and health (Twinley, 2017). These occupations may not be prosocial, healthy or productive, but they may still have meaning and purpose to the individual (Kiepek & Magalhaes, 2011; Twinley & Addidle, 2012).

In the use of the term “dark side of occupation” Twinley sought to acknowledge the lack of attention to the occupation, and the resultant lack of understanding, not pass judgement on the occupations themselves. As a result, occupations are not described as dark per se, but inhabiting an unilluminated place in our professional attention (Twinley, 2017; 2020). Some specific occupations, as diverse as substance misuse (Keipek et al, 2022), beauty pageants (Sy, Martinez & Twinley, 2021) and sex work (Huglstad et al, 2020) have been linked with the dark side of occupation. However, many occupations have the potential to be explored using this lens. Occupations may be in the shadows for many reasons (Nicholls & Elliot, 2021) and what shapes perceptions of an occupation is often nuanced. Attitudes can reflect the nature of the occupation itself, the way the person engages with it and external attitudes towards the occupation or the person performing it.

Occupation and the judgement of others

In considering the person-environment-occupation triad there has often been limited focus on the social context of engagement. However, attitudes towards people and what they do can be a major influence on experiences of an occupation. For example, alcohol consumption is legal and widely socially accepted in many countries, though it is recognised as having significant personal and social harms. We may view drinking alcohol differently on the basis of how much a person drinks, how much harm it does to them or others and how it effects their performance in work and family life. However, we may also judge the behaviour on the basis of features such as age, gender, ethnicity and social class, with other prejudices framing attitudes towards behaviour (Lennox et al. 2018). This means that the same activity, with potentially the same harms, can elicit very different social responses on the basis of moralising, discrimination and prejudices (Pooley & Beagan, 2021).

Another example of prejudice-based occupational disparities can be seen in the discourse “Living while Black”. Senior Editor at CNN Brandon Griggs (Griggs, B. 2018) describes a myriad of instances where black people in the US were reported to the police whilst engaging in everyday activities – including golfing too slowly, waiting for a friend, working out, moving into an apartment, shopping for prom clothes, asking for directions, eating lunch on a college campus, helping a homeless man, delivering newspapers, swimming in a pool, and driving with leaves on a car. These behaviours do not appear to be inherently problematic but have been interpreted as such due to the ethnicity of the person performing them. The people reporting these everyday behaviours have judged (and criminalised) not the occupation, but the person performing it. This would suggest that much of what relegates an occupation to the shadows lies in the perception of others and their “social sanctioning” of the activity (Kiepek et al. 2019) – judging the individual or group performing the behaviour, rather than the behaviour itself. The role of prejudice and discrimination in occupation is becoming increasingly acknowledged, as it creates barriers to performance and shapes professional and public attitudes towards what people do and forms key occupational injustices (Lockmiller & Armstrong-Heimsoth, 2022; Pooley & Beagan, 2021).

Exclusion and hidden occupations

When individuals and occupations are judged and interpreted differently this shapes peoples’ sense of their occupational possibilities. Often people who already feel excluded can find it harder to enter into a new occupation, fearing judgement or feeling unwelcome. Jung identified the shadow of the self as everything outside the light of consciousness (Jung, 1938). A natural part of the individual, positive or negative, the shadow could be challenging because it was less openly integrated: “Everyone carries a shadow, and the less it is embodied in the individual's conscious life, the blacker and denser it is” (Jung, 1938, p.131). Similarly, the more judged an occupation (or the person enacting it) the more hidden it becomes, pushing it into the shadows. The more a person feels like “misfit” in a context the more pressure there is to performatively “fit in” (Beagan et al. 2022), forego opportunities or hide their chosen occupations for fear of being judged (Balliard, 2013).Feelings of shame are often deeply embedded as a result of marginalisation (Lockmiller & Armstrong-Heimsoth, 2022) creating feelings of oppression through lack of self-belief, practical exclusion, stigma, or prejudice. This creates both internal and external exclusion, which can be overt, such as governmental policies preventing legal work for people seeking asylum. Such policies directly prevent occupational engagement and increase the risk of people engaging in illegal, dangerous and exploitative work (UNHCR & British Red Cross, 2022). Alternatively, barriers may be more subtle, such as the socio-cultural influences on exercise for South Asian women, which limit their comfort in accessing health promoting activities (Bhatnagar, Foster & Shaw, 2021).

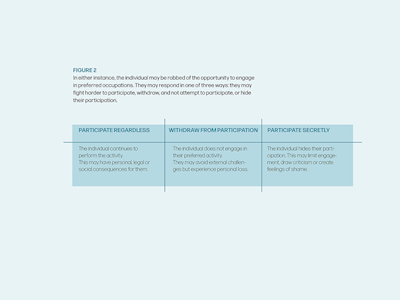

In either instance, the individual may be robbed of the opportunity to engage in preferred occupations. They may respond in one of three ways: they may fight harder to participate, withdraw, and not attempt to participate, or hide their participation.

This is likely to create circumstances where only the most courageous, energetic individuals, or those with the least to lose, feel able to engage fully. For a large proportion of people, their occupational desires go unknown and their needs unmet. Hiding one’s occupation to avoid judgement can increase the individual’s sense of separateness and isolation, creating feelings of guilt and shame and making it difficult to seek support. It can encourage people to disengage from wider society and seek out people and places where they will not be judged, creating increased marginalisation and further exclusion (Beagan et al. 2022; Lockmiller & Armstrong-Heimsoth, 2022).

Occupation can become an extension of “contingent self-esteem”, where the individual’s own sense of self-worth is determined by external factors such as the approval of others and social comparison (Crocker & Knight, 2005). Contingents may vary, but are often focused on relationships or perceived success (Schone et al. 2015). Occupation can be a mean of demonstrating worth and creating contingent self-esteem, but the more excluded the individual is the harder it becomes (Hart, 2018). This connection between individual, occupation and attitude can shape the landscape of possibilities available to a person, limiting their occupational choice, particularly if they are part of an existing “outgroup” (Bailliard, 2014; Galvaan, 2012; 2015; Hart, 2018).

Using a new lens and mirror

Occupational therapy cannot be a truly holistic, client-centred and occupation-focussed without acknowledging a broad range of occupations, as experienced by a broad range of individuals (Twinley, 2017). Unchallenged, our theory and philosophies could impose perspectives on “ideal” ways of living (Al Busaidy and Borthwick, 2012; Kantartsis and Molineux, 2011) or focus only on the occupations that support out idea of positivity, productivity, and health (Pierce, 2o12). This has negative political, practical and theoretical implications (Castro, Dahlin-Ivanoff & Nartensson, 2014) and reduces our potential to be inclusive and social relevant (Pierce, 2012; Twinley and Addidle, 2012).The dark side of occupation provides a new “lens and mirror” for the exploration of occupation (Hart, 2020). As an additional lens, it helps us to see the diverse nature of occupational engagement, making visible the inequities built into everyday lives (Beagan et al. 2022). As mirror, it allows us to reflect and acknowledge our role in the maintenance of oppression and marginalisation, recognising that the more excluded a person is the harder it is for them to exercise occupational choice (Galvaan, 2015; Hart, 2018; Hammell, 2020). This is essential if we are to acknowledge the role of personal and social context in occupational opportunities and use it as a call to action (Pooley & Beagan, 2021; Beagan et al. 2022).

References

Al Busaidy, N. S. M. and Borthwick, A. (2012) ‘Occupational Therapy in Oman: The Impact of Cultural Dissonance’, Occupational Therapy International, 19, pp. 154–164.Bailliard, A. (2013) Laying Low: Fear and Injustice for Latino Migrants to Smalltown, USA, Journal of Occupational Science, 20:4, 342-356, DOI: 10.1080/14427591.2013.799114

Beagan, B.L., Sibbald, K.R., Pride, T.M., and Bizzeth, S.R. (2022) "Professional Misfits: “You’re Having to Perform . . . All Week Long”. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy 10(4) pp. 1-14.

Bhatnagar, P., Foster, C., and Shaw, A. (2021) Barriers and facilitators to physical activity in second-generation British Indian women: A qualitative study. PLoS One. 16(11):e0259248. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0259248.

Castro, D., Dahlin-Ivanoff, S. and Mårtensson, L. (2014) ‘Occupational therapy and culture: a literature review’, Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 21(6), pp. 401-414.

Crocker, J., & Knight, K. M. (2005). Contingencies of Self-Worth. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(4), 200–203. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20183024

Galvaan, R. (2015) ‘The Contextually Situated Nature of Occupational Choice: Marginalised Young Adolescents' Experiences in South Africa’ Journal of Occupational Science, 22(1), pp. 39-53.

Griggs, B. (2018) Living while black, https://edition.cnn.com/2018/12/20/us/living-while-black-police-calls-trnd/index.html

Hammell, K.W. (2017) Opportunities for well-being: The right to occupational engagement. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2017;84(4-5):209-222. doi:10.1177/0008417417734831

Hammell, K.W. (2020) Making Choices from the Choices we have: The Contextual-Embeddedness of Occupational Choice. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2020;87(5):400-411.

Hart, H.C. (2020) ‘The Whole of the Moon: how seeing the dark side of occupation can develop our use of conceptual models of practice.’ In: Twinley, R. Illuminating the Dark Side of Occupation: International Perspectives from Occupational Therapy and Occupational Science. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Hart, H.C. (2018) ‘Keeping busy with purpose: Virtuous occupations as a means of expressing worth during asylum’, PhD Thesis, Teesside University

Huglstad, M., Halvorsen, I.L.I, Jonsson, H. & Nielsen, K.T. (2022) “Some of us actually choose to do this”: The meanings of sex work from the perspective of female sex workers in Denmark, Journal of Occupational Science, 29:1, 68-81, DOI: 10.1080/14427591.2020.1830841

Jung, C.G. (1938). On the Psychological Aspects of the Mother Archetype. Collected Works (Vol. 9). Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kantartzis, S. and Molineux, M. (2011) ‘The Influence of Western Society's Construction of a Healthy Daily Life on the Conceptualisation of Occupation’, Journal of Occupational Science, 18(1), pp. 62-80.

Kiepek, N., and Magalhães, L. (2011) ‘Addictions and impulse-control disorders as occupation: A selected literature review and synthesis addictions and impulse-control disorders as occupation’. Journal of Occupational Science, 18, pp. 254-276.

Kiepek, N., Ausman, C., Beagan, B., & Patten, S. (2022). Substance use and meaning: transforming occupational participation and experience. Cadernos Brasileiros de Terapia Ocupacional, 30, e3037. https://doi.org/10.1590/2526-8910.ctoAO23023037

Kiepek, N., Beagan, B., Laliberte Rudman, D. & Phelan, S. (2019). Silences around occupations framed as unhealthy, illegal, and deviant. Journal of Occupational Science, 26(3), 341-353. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2018.1499123

Lennox, J, Emslie, C., Sweeting, H. and Lyons, A. (2018) The role of alcohol in constructing gender & class identities among young women in the age of social media, International Journal of Drug Policy, 58, pp. 13-21, doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.04.009.

lockmiller, m., & Armstrong-Heimsoth, A. (2022). Finding a Voice: Overcoming Shame Through a Classroom Collective Exploration of Vulnerability. Journal of Occupational Therapy Education, 6 (1). doi.org/10.26681/jote.2022.060116

Nicholls, L. & Elliot, M.L (2019) In the shadow of occupation: Racism, shame and grief, Journal of Occupational Science, 26:3, pp. 354-365, doi: 10.1080/14427591.2018.1523021

Pierce, D. (2012) ‘The 2011 Ruth Zemke Lecture in Occupational Science’, Journal of Occupational Science, 19(4), pp. 298-311.

Pooley, E.A., and Beagan, B.L. (2021) The Concept of Oppression and Occupational Therapy: A Critical Interpretive Synthesis. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 88(4):407-417. doi:10.1177/00084174211051168

Reitz, S. & Scaffa, M. (2020). Occupational Therapy in the Promotion of Health and Well-Being. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 74. 7403420010p1. 10.5014/ajot.2020.743003.

Schöne, C., Tandler, S.S., Stiensmeier-Pelster, J. (2015) Contingent self-esteem and vulnerability to depression: academic contingent self-esteem predicts depressive symptoms in students. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, DOI=10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01573

Sy, M.P., Martinez, P.G.V., Twinley, R. (2021) The dark side of occupation within the context of modern-day beauty pageants. Work. 69(2):367-377. doi: 10.3233/WOR-205055.

Twinley, R. (2017) 'The Dark Side of Occupation', in: Jacobs, K. and MacRae, N. (eds) Occupational Therapy Essentials for Clinical Competence. 3rd edn. Thorofare, NJ: SLACK, pp: 29-36.

Twinley, R. and Addidle, G. (2012) ‘Considering Violence: The Dark Side of Occupation’, British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75(4), pp. 202-204.

Twinley, R. (2020) Illuminating The Dark Side of Occupation: International Perspectives from Occupational Therapy and Occupational Science. Abingdon: Routledge.

UNHCR & British Red Cross (2022) At Risk: Exploitation and the UK Asylum System - A Report by UNHCR and The British Red Cross https://www.unhcr.org/62ea90d2bc